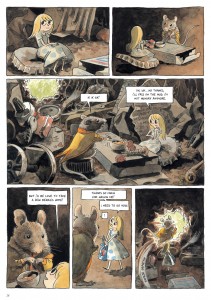

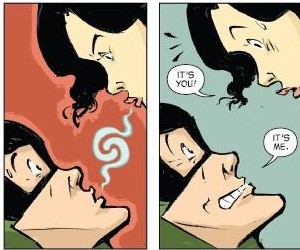

In America it's the 4th of July, which means a fair amount of our readership is out baking in the sun and knocking back bad beer. It seems like as good a time as any to drop an unpopular review. The Shadow Hero is reclaiming an obscure Golden Age hero with the aim of exploring his never revealed origin. In short, it's an American comic book with an Asian-American lead. (File that under Rarer Than Domesticated Unicorns.) Yang and Liew are relentlessly talented. The Shadow Hero is expertly paced. Clever sight gags mix with atmospheric panels to create a constantly moving sense of space. It also tackles racism in a way that tries to be nuanced but feels recycled. The Shadow Hero's origin story is six parts Ancient Chinese Secret and four parts Mommy Issues with a dash of Fated Mate sprinkled across the top.

This graphic novel is tagged for ages 12 to 18. I'm not sure this age range will make the distinctions Yang and Liew demand. When a number of characters tell Hank he hits like a girl, providing girls who can fight doesn't erase the sexism reinforcement. Even the girl herself tells Hank he hits like a girl. She doesn't tell him he hits like a boy or that he hits without full force. (Serving as an exception isn't refuting an ism.) I gave this book to a group of teens in the targeted age range and discussed it with them afterward. None of them picked up that Yang intended three of the female characters to disprove the sexism. Several of the racist conventions being explored and subverted were new to them as well. While this was a group of primarily white teens who may not be exposed to the same racist concepts as others, it made me consider if The Shadow Hero is appropriately targeted. My take on the use of Tongs and secret gambling dens might be different if the book was aimed at an adult readership.

I was also disappointed that Hank's growth involves completely changing who he is. When we meet him he's a pacifist longing for a simple life of domesticity. Hank greatly admires his father, a man who prefers simple sober living to warfare. His mother dreams of different things, and it is her vision of Hank that prevails, despite her being the distant and less obviously loving parent. Hank strives to keep her attention and in doing so becomes the opposite of who he once wanted to be. The book doesn't leave this for the reader to judge. The text continually reinforces that a pacifist life is for cowards. Everyone successful in The Shadow Hero lives a life of violence or fear. Hank's longing for tranquility is exposed as an unworthy goal.

All of that aside, I still consider The Shadow Hero a must read book. The send up of some superhero conventions are pitch perfect. The characters, aside from the Fated Mate, are individual and fully imagined. Hank's story, as well as those of his parents, is emotionally compelling. His mother's frustrated dreams, arising as much from her own poor choices as from fate, are heartbreaking in their effect on Hank's future. I wish Yang and Lieu had imagined an origin story with less Dragon Ladies and more innovation, but taking The Shadow Hero as a whole it's worth investigating. When I closed the book I didn't feel the need for the story to continue but I was glad I'd experienced it.

All of that aside, I still consider The Shadow Hero a must read book. The send up of some superhero conventions are pitch perfect. The characters, aside from the Fated Mate, are individual and fully imagined. Hank's story, as well as those of his parents, is emotionally compelling. His mother's frustrated dreams, arising as much from her own poor choices as from fate, are heartbreaking in their effect on Hank's future. I wish Yang and Lieu had imagined an origin story with less Dragon Ladies and more innovation, but taking The Shadow Hero as a whole it's worth investigating. When I closed the book I didn't feel the need for the story to continue but I was glad I'd experienced it.

*This review originally appeared at Love In The Margins.